Page Content

Hunger March, Calgary Alberta (1932), Photographic Collection,

Provincial Archives of Alberta, object number A2915.

More than a name on a building

The following is based on “A Short Memoir” by A.J.H. Powell, who served as ATA president from 1929 to 1930. The article has been edited for length and content. The original article, written in 1962, is housed in the ATA’s archives. Powell died in 1987.

The following is based on “A Short Memoir” by A.J.H. Powell, who served as ATA president from 1929 to 1930. The article has been edited for length and content. The original article, written in 1962, is housed in the ATA’s archives. Powell died in 1987.

Everything under control

It was the worst of times. Submarine and surface blockade had long since inured the people of Europe to marginal nutrition and all-pervading austerity. The long-dragging anxieties of war were already weakening millions for a visitation of the Spanish Flu. The Western Front had just caved in on the Somme River.

It was the worst of times for inaugurating a new workers’ association. In North America, the chronic feud between the International Workers of the World and the American Federation of Labour and the struggles of both for civilized working conditions had stirred the press to new heights of rhetorical abuse; and the Red Revolution in Russia had given the newspapers a new epithet, BOLSHIE, to smear on all workers who wanted a fair share of anything. Under the impact of their wordy assault, the minds of solid citizens everywhere were hardened against unions and outside agitators.

To all appearance, the good people of Alberta had, in this nadir of World War I, little to fear about the unionizing of their teachers. There was an Alberta Educational Association (A.E.A.), fathered by the Department of Education and gently chaperoned by its officials, which put on each year a teachers’ convention during Easter week. The convention was held alternately in Calgary and Edmonton. It featured a distinguished speaker who gave three addresses, and filled in the three-day program with talks on philosophical and curricular topics, by teachers, normal school instructors and UofA men. Eminent speakers in those days included President Suzallo of Washington, President Tory and Dean Boyle of the UofA, Dean Quance of Saskatoon and Rev. Dr. George W. Kerby of Mount Royal College in Calgary. As an inspirational offering, the Easter conventions of the Alberta Educational Association were excellent; many of us still recall those fine gatherings in Central Church, Calgary, and in McDougall Church, Edmonton, when the galleries and choir lofts were packed with teachers and laymen. Charlie Leppard of Calgary was the perennial secretary of the organization and deserves to be kindly remembered.

Supplementing the Easter convention we had in those days, the fall convention in each inspectorate, sponsored by the Department, chaperoned by the inspector, and managed by an ad hoc executive named for the ensuing year at the close of each convention. Here again the purpose was inspirational and instructional; we listened eagerly to speakers from the university and the normal schools, to local ministers and doctors, and of course to the inspector. Such mundane matters as credits for summer courses or salary negotiations were never mentioned. There were no salary schedules to discuss.

This pattern of provincial and local teachers’ conventions was (and doubtless designed to be) a neat device for keeping teachers on their good behavior. In these they had their organization; here they could meet and find fellowship. There was no need, no legitimate right of the teachers which, in the opinion of the Department, could not be met or fostered by the A.E.A. and the local conventions, with the Department’s officials in paternal control.

But the winds of change were blowing chilly.

The war baby of 1918

The winds of change were blowing chilly. As far away as England, a commission headed by Lord Burnham was studying the economic plight of teachers and compiling a report and a schedule of salaries known to this day as the Burnham Scale. The scale was modest, but it moved the teachers at one bound out of penury into the middle class.

Ontario had its teacher organizations, whose power was manifest in good salary schedules and adequate pension plan. Manitoba was organized and Saskatchewan was stirring. The British Columbia Teachers’ Federation (B.C.T.F.) was a going concern with Harry Charlesworth as general secretary already working up a pension drive.

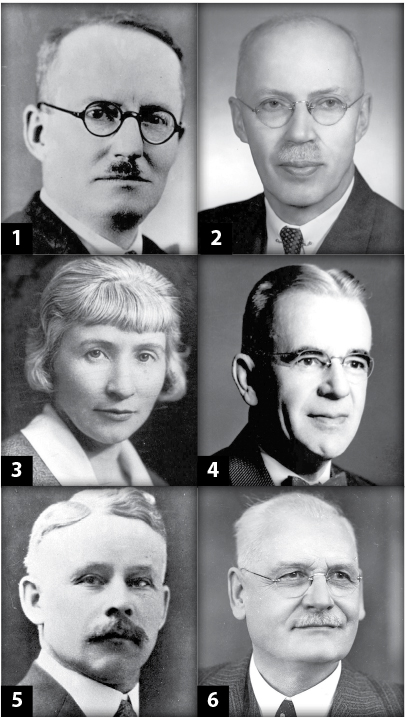

Alberta teachers knew of these things. Englishmen like Lionel Gibbs, Matt Hilton and John Barnett were well informed about the English development. There were graduates of Toronto and McGill on our staffs: Ross Sheppard, C.O. Hicks, H.C. Newland, Harry Balfour, Mary Crawford and George Misener, to name a few. These people knew what went on in the world, and were not satisfied with what they saw going on at home.

There were no salary schedules worth the name, and no such thing as collective bargaining. At the beginning of World War I, the Edmonton School Board had, unilaterally and without consultation with the teachers, voted a stiff percentage of their salaries to be contributed to a national servicemen’s welfare fund. Teachers had no organization capable of either opposing or redressing such brigandage. While the stresses of war raised the price of everything, there were no channels of negotiation for pay increases. Throughout the province, the outlook was discouraging. Children of grade ten standing were teaching rural schools by letter of authority, and a mixed bag of recruits from east and south was offering patchy service. School buildings were poor and cold, supplies meagre, books at a minimum, playground equipment nil.

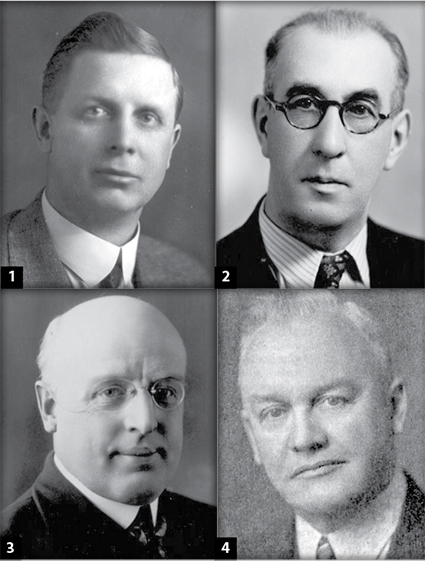

1. H.C. Newland, 2. Harry Balfour, 3. Mary Crawford, 4. George Misener, 5. T.E.A. Stanley, 6. John Barnett

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

It would be interesting to know how the spark of protest grew to a flame, and where. Did Newland, Balfour, Misener and Crawford plot treason in the little staff room at old Vic High? Did Barnett fan revolt as he went on his rounds as assistant music supervisor? Was there a sudden flaming of minds as the Edmonton crowd rode the day train down to Calgary for the Easter convention of the A.E.A. in 1918? Or did the fire burn first in the souls of T.E.A. Stanley, Fred Parker, Jennie Elliott and others of the Calgary staff? And when they got into the sedate doings at Central Church, what were their plans? Did they erupt in one of the inspirational mass meetings with a resounding resolution, only to be told there was no place on the A.E.A. agenda for such subversive capers?

This writer was not present at the birth of the Alberta Teachers’ Alliance (he was in France, digging trenches to help stop Ludendorff’s breakthrough). Many of the early stalwarts are gone, including the first president of the A.T.A., George Misener, and the first permanent secretary, John Barnett.

Out on the trails

And so John Barnett became the first fulltime general secretary of the A.T.A. He hailed from Grantham, in Lincolnshire, a man of fine physique and features with a rather swashbuckling dark moustache. He stood about six feet and carried 190 pounds gracefully. In England, he had been an army schoolmaster and had played soccer with one of the leading league teams, Aston Villa. His teaching career in Canada showed interesting variety: a rural school in the Seggewick area, where he struck up a lifelong friendship with George Andrews, M.L.A. (United Farmers of Alberta, U.F.A.) and perennial secretary of the Alberta School Trustees’ Association; commercial subjects at Strathcona High School under principal George Albert McKee; and assistant city supervisorship of music under Norman Eagleson.

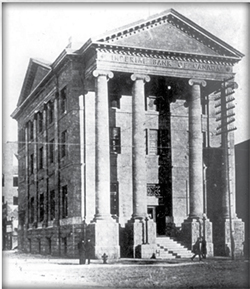

In the early days, John kept office in his home on 107 Street opposite the southwest corner of the Queen Alexandra campus, Edmonton, where Mrs. Barnett and the four young children took innumerable phone calls for him during his many lengthy absences. After a year or two of this, John moved his office to the top of the old Imperial Bank Building at Jasper and 100 Street. This quaint colonnaded structure dated back to times when banks provided living quarters over their premises for their bachelor employees to keep them out of saloons, pool halls and gambling dens. This custom had lapsed, and John was able to rent first one and later several rooms to meet the growing needs of the young Alliance, at little more than a nominal charge. He remained there over twenty years, climbing three long flights of stairs at a speed none of us softer mortals could challenge. During World War II, he had to move out to tiny quarters in the warehouse district. After the war, he came back for a while to his old eyrie, but he never did see the fine new home of the organization, named in his honor, Barnett House.

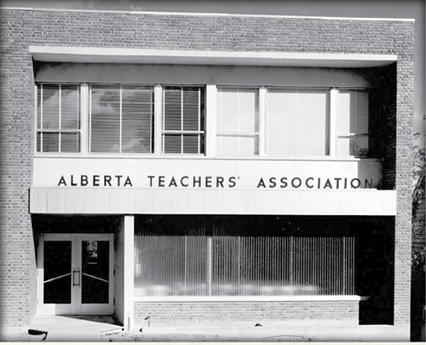

Alberta Teachers’ Association headquarters, 103 street, Edmonton, circa 1950s

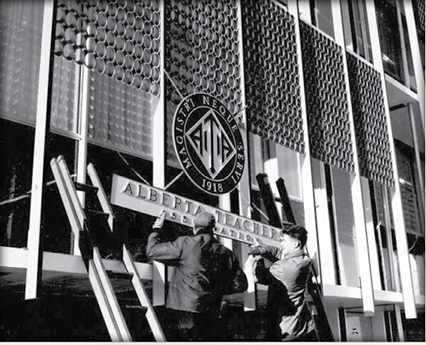

Alberta Teachers’ Association headquarters, 11010-142 Street, Edmonton, circa 1968

Alberta Teachers’ Association headquarters, 11010-142 Street, Edmonton, circa 1968

Alberta Teachers’ Alliance headquarters, upper floor of Imperial Bank Building, Jasper Avenue and 100 Street, circa 1920s

Alberta Teachers’ Association staff member counting ballots, circa 1950s

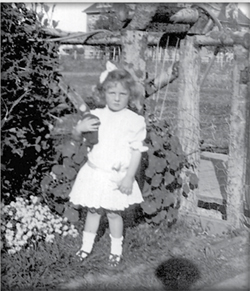

Daughter of J.W. Barnett posing in yard of Barnett home, 107 Street, Edmonton. In the background is Queen Alexandra School, circa 1920s

Daughter of J.W. Barnett posing in yard of Barnett home, 107 Street, Edmonton. In the background is Queen Alexandra School, circa 1920s

Many teachers in the earliest days were eager to mount their fiery steeds and ride off in all directions, but John quickly realised that all other activities would have to wait upon the signing of memberships and collection of dues. He himself would have to be canvasser and collector. The four major cities could be relied upon (with some prodding) to organize from year to year and sign up fifty percent or better of their teaching staff. Even in the cities it was often necessary for John to make personal visits and galvanize the local officers into movement. But the dues levied in those days—five dollars per annum—did not amount to much from about six hundred city teachers. Barnett had to maintain his own home and family, pay office rent and secretary, build up the office equipment from scratch, pay postage and meet the costs of his frequent road trips. He might wait in his office till Doomsday and the money to keep the Alliance alive would never come in. He would have to go out on the trails and sell the A.T.A. to one teacher at a time.

John Barnett’s constituency consisted of 5,000 teachers scattered from Fort Smith in the north to Whiskey Gap in the south; from Jasper in the west to Lloydminster in the east; and he had to get out and sell to them the idea of professional solidarity—an idea priced at five dollars—in competition with vendors of Watkins products, Rawleigh liniments, doctor books and Wearever aluminum. Either sell the idea or go back to his classroom.

It is doubtful if so Herculean a task of teacher organization has ever been successfully pulled off elsewhere. In Saskatchewan, the effort was made for some years, but the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Association died during the Great Depression. In Manitoba, the Manitoba Teachers’ Federation rode on the shoulders of Winnipeg with rural teachers remaining in outer darkness. B.C.T.F. was carried by Vancouver and Victoria, but reached out with much more vigor to the hinterland teachers. Perhaps in Australia a comparable job was done? Not by any means. In every Australian state the population is heavily concentrated in one or two metropolitan areas, easy to reach and organize. So John Barnett’s task and his achievement were probably unique.

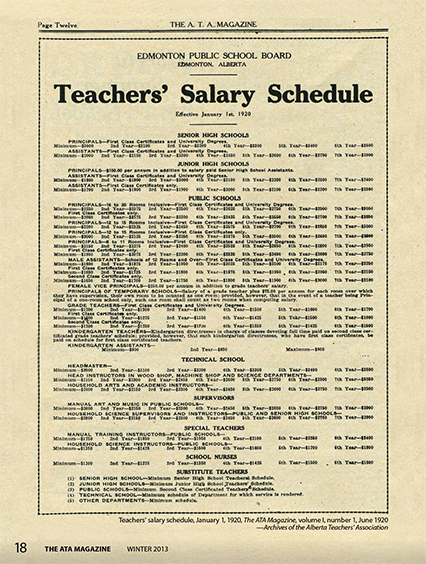

Teachers’ salary schedule, January 1, 1920, The ATA Magazine, volume I, number 1, June 1920

—Archives of The Alberta Teachers’ Association

Every September, as soon as he felt teachers had had time to shake down in harness, John would set off down the Calgary trail in his Gray Dort (or McLaughlin or Jewett or Buick) and make his call at every town and whistle stop. After canvassing the local staff, he would inquire who was in this or that school of the surrounding countryside. Armed only with their names, he would turn his car off into the wagon-tracks and visit them. His “prospects” were of every type from excellent to hopeless. Here was a local girl who needed no job insurance because Dad was on the school board. Here was an old-countryman steeped in the National Union of Teachers tradition and glad to do business with John. Here was a small-town principal who was trying to buy a house, finance a Ford and raise a young family; he honestly did not see how he could spare five dollars. Here was a young lady whose father had firmly warned her to stay out of the Alliance—“just a bunch of reds.” Here was a girl whose pay was long in arrears from her last school; she didn’t mind gambling five dollars on the chance that John could collect for her. Here was a young lady who just disliked “that man” and had sworn mutual oath with her buddy along the correction line that she wouldn’t let J.W. Barnett pry a membership fee out of her. And here and there were those who listened to John’s appeal and signed up willingly.

During those early years, there were numerous towns and some inspectorates in which John had a discouraging battle to fight. It has already been said that the Department had relied confidently upon its Alberta Educational Association and the fall conventions to head off any radical self-organization measures by the teachers. When the teachers found themselves an able and aggressive leader, Deputy Minister John T. Ross did not at all conceal his displeasure, while his political chief, the Hon. George Peter Smith, assumed an air of light-hearted contempt towards the Alliance. It was, he said in an off-color allusion to a back-room story, “forever blowing bubbles!” In fact he was so forthright in derision of the A.T.A. that Barnett took counteraction. In the final days of the 1921 provincial election campaign, John spent two days in the U.F.A. Camrose headquarters assisting in the fight to oust George Peter. (It may be doubted whether his help was necessary or important. The U.F.A. swept the province.)

John Edward Brownlee, Premier of Alberta (United Farmers) (1925–1934) (circa 1932), Photographic Collection, Provincial Archives of Alberta, object number A21149

The new U.F.A. minister of education was Perren E. Baker, a successful dry farmer from the southern Cypress Hills, a former church minister and a graduate of McMaster University. His ear was finely tuned to the sentiments of the farming people who would be keeping him in power, and these sentiments did not often harmonise with those of the urban teachers whose voices were most clearly heard in the A.T.A. Moreover, Baker did not mistake the feelings of his deputy about this upstart Alliance. He therefore never allowed himself any expression of warmth or approval towards our organization until the last years of the John E. Brownlee government.

There is a point to this small historical digression. It is quite normal for persons in subordinate positions, with a healthy desire for advancement, to take notice of the likes and dislikes of those above them, and to govern themselves discreetly. This was widely true among teachers and administrators in Alberta. At least one normal school principal, several inspectors, numerous principals and many teachers took their cue from the top men, and the A.T.A. made little progress among them. Fortunately, there were many influential men in administration and local leadership who thought for themselves, who had seen professional organization in action back in Ontario or elsewhere and who were willing to help the young Alliance fight for its life in a fair field.

More and rougher trails

Few teachers remember the Alberta roads of the early Twenties. In the major cities, there was a useful skeleton of hard-top main thoroughfares, though couch grass still flourished between the streetcar rails. The main stem from Edmonton to Calgary was prairie soil cambered enough to shed water; so were the busier lateral roads eastward to Saskatchewan. But the first hard surfacing material outside the city limits was not applied until 1925. It consisted of 19 miles of egg-sized gravel laid to a depth of nine inches between North Edmonton and Fort Saskatchewan. Within a year or so, a similar surface reached from Edmonton to Calgary. It was soon rolled down sufficiently to form a useful all-weather highway, provided one looked out for loose gravel patches and for dangerous potholes at the ends of trestle bridges. And it must be remembered that for many years this highway or long stretches of it, fell to ruin with every spring thaw.

Horses pulling automobile out of impassable Alberta road (1928), Provincial Archives of Alberta, Photographic Collection, object number AC183

Cross-country driving could be heaven or hell, depending on the weather. In a dry summer with the road well dragged, the going was good so long as one kept ahead of the other fellow’s dust. One took the right-angled turns slowly, for there were Death Corners of dreadful repute in those days, and one met or passed carefully skirting the soft shouldered ditch. But in the spring thaw or a rainy spell, there was nothing to mitigate the sheer misery of driving on the Alberta secondary roads, unless it was a mile or two of sandy road here and there. Put on your chains, grind your way through and stay out of the ditch.

This writer recalls riding with John Barnett and a carload of Executive men down to Calgary for the A.G.M. of 1928. We left John’s home in his ancient Jewett at 8 a.m., stopped for a leisurely lunch at Red Deer, and after a grim and hazardous trip, arrived at the York Hotel in Calgary at 7:30 p.m.

It was on these diverse and unpredictable roads that our first general secretary drove out each year for twenty years to build and rebuild the Alberta Teachers’ Alliance.

William A. Stickle

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

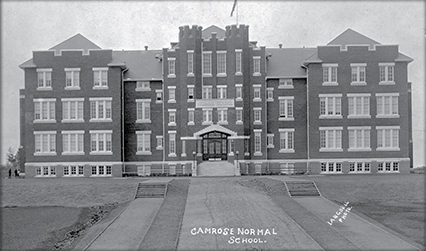

Now we can rejoin John Barnett and his Gray Dort. He has veered eastward from Wetaskiwin, and after combing the countryside around Meeting Creek and New Norway he drives up to the front door of the Camrose Normal School. This will be one of his happier days. The principal is William A. Stickle, who takes his opinions from nobody but thinks it is time the teachers organize themselves. He has had notice of Barnett’s visit and at 3:30 p.m. the student body and staff are assembled in the auditorium. The principal introduces John so warmly that not only the students but all the teachers know where Stickle stands. Barnett makes his appeal on sound philosophical grounds and then offers recruit memberships at one dollar per student. He expounds the provincial A.T.A. policy of a minimum salary of $1,000 per year, and urges all the students to accept no less. Before closing his address, he obtains from the floor the names of five students who are to be the executive of the Camrose Normal School local. A future president of the provincial Alliance is one of the five. When the assembly is dismissed, John meets this executive and gives it a forty-minute briefing.

After signing in at the Arlington and eating a hearty dinner, John calls upon the high school and practice school principals to set up cordial relations with them, and then drops in to see his old friend Inspector John Russell from whom (after some swapping of yarns) he gets names and particulars of outlying schools and their teachers. This Barnett is no nine-to-four operator. This writer recalls riding out with him to an evening rally at Radway Centre. As we came back into Edmonton on the north road it was 11:30 p.m. but John did not head for the High Level Bridge and home. Instead, he turned left to the Corona Hotel to catch a few minutes with the M.L.A. from Warner and ensure his support for a clause relating to the Teachers’ Reference Board, due to come up in the legislature the next day. He found his man in the rotunda and worked on him for thirty-five minutes. Then we drove home.

Barnett’s normal school visits were not always as cordial as the one just related. At one normal school, his credentials were rejected and he was denied permission to address the students. It was not until he had wrung from a reluctant minister an order for his admission and proper reception that he was able to deliver his message and set up his A.T.A. local in that school.

Camrose Normal School (1916), Provincial Archives of Alberta, Photographic Collection, object number A11923

South from Camrose, John would work down through Drumheller towards Calgary, all the way meeting and canvassing teachers—willing, reluctant, hard-up, lonely, indifferent, unpaid, cordial, harassed or stepping-stone teachers. There were hundreds of these latter teachers looking for a bright young farmer to marry. Other teachers were financing themselves through medicine, dentistry or law; teachers who hoped to buy shares in a little store or even a beer parlor; teachers who saw no future in teaching. With few exceptions they were saving (with that dedicated penurious thrift the pioneers knew so well) to get into something else. John Barnett or anyone else would have a hard time trying to sell them five dollars’ worth of professional solidarity.

T.E.A. Stanley

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

He would arrive in Calgary in time for a regular meeting of the Men’s and/or Women’s local. There he would give a comprehensive survey of all A.T.A. work and of the legislative targets set by the provincial Executive for improving salaries, tenure and prestige. If necessary—it was often urgently so—he would appeal for an immediate membership drive in every school and for prompt payment of dues to the head office. Before leaving town, he would renew friendships with the stalwarts, T.E.A. Stanley, W.W. Scott, Fred Parker and others; and perhaps make contact with other sound fellows who seemed coy about accepting office or leadership. The same job had to be done at Lethbridge, with a busy round of calls on A.J. Watson, Harry Sweet, George Watson and others; and at Medicine Hat, where the reliables included Charles Peasley, Mary Fowler, David M. Sullivan and Eric Ansley. Sometimes John would journey as far south as Cardston or Manyberries, but too frequently the pile up of trouble cases and other crises brought him hurrying by way of Innisfail and Red Deer back to Edmonton.

The office help consisted in the early days of Miss Margaret Benham, who was assisted after a few years by Mrs. Grace Devon. Mrs. Devon was a loyal and competent stenographer, but it was Miss Benham who shortly became a most astute and capable understudy of the general secretary. She sat in at all A.G.M.s and all meetings of the Executive and Law Committee, and mastered every intricate point of school law and procedure. Her management of the office during John’s frequent road trips and her efficiency made a valuable contribution to A.T.A. growth and progress. Miss Benham left us to join one of the women’s auxiliary services during World War II.

So John would get home from his membership campaign, work through his in-basket with Miss Benham and then phone the A.T.A. president: “Barnett here. How are you? Well, we can eat for another year, say till next October. There are 1,853 memberships in so far and that will be up to 2,400 when all the fall conventions have been covered.”

Golden Rod School, Airdrie, Alberta (1919), United Church Photographic Collection, Provincial Archives of Alberta, object number UC47

And of course the fall conventions were covered. Many of them John attended himself, making his appeal and setting up two or three executives to foster locals in the small towns. He would personally canvass all the teachers in attendance. To other conventions he would send teacher-agents from the Executive—Harry Ainlay, Harry Clarke and A.J.H. Powell. These had varying success in collecting dues, but as the years went on they blanketed Alberta with news of the Alliance.

1. Harry Ainlay, 2. Harry Clark, 3. William Aberhart, 4. George F. McNally

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

It must not be overlooked that the huge task of building the financial sinews of the A.T.A. had to be done afresh each year from 1918–1937, when automatic membership and Departmental handling of dues were inaugurated. There was no rest or surcease for Barnett during those twenty years. If he had once balked at that long, exhausting fall campaign, the young Alliance would have died. As it was, John nearly died early in the story. After one of those strenuous drives in stormy weather, he went to bed with pneumonia (this was before the word antibiotic was heard) and only John’s fine constitution and fighting spirit saved his life.

Giving service

We have seen some of the physical and psychological difficulties under which the general secretary laboured in building and rebuilding the Alliance year after year. Perhaps the greatest challenge for Barnett in those early years lay with rural teachers. While city teaching staffs had become established, the rural and village teachers were still a transient lot. They passed through normal school, taught just long enough to repay their government loan, and then married or went into other activities. (In those days, it was considered unthinkable for a married woman—unless widowed or divorced—to hold a teaching job.) The average teaching career of those in rural and village areas was thus from two to three years. This meant that the task of indoctrinating the teaching body with professional solidarity had to be pursued without pause to gain recruits in place of the annual exodus.

The best way to do this was to render service and publicize the service. One good field of opportunity lay in the collection of overdue salaries. Farmers all over the west had expanded their holdings in land and equipment during the war years of “two-dollar wheat” and when in 1921 it became one-dollar wheat, they became hard-pressed, penurious and discouraged in outlook. Tax delinquency became more or less rampant, and the boards managing the little white school houses became increasingly dependent upon the government grant for their running expenses. All too often the teacher, hired at the minimum salary of $840 a year, received the grant and no more.

One by one and later by the dozens, teachers began to learn that the A.T.A. would take necessary action to recover overdue salary for them, even after they had quit the delinquent district and gone elsewhere. Barnett established a routine: a lawyer’s letter, a follow-up letter, a clearance with the A.T.A. Law Committee, and then if necessary a civil action against the school board, which invariably got the teacher her money.

Not all teachers had the initiative to seek A.T.A. help. In 1936/37, when Premier and Minister of Education William Aberhart and Deputy Minister George F. McNally were pushing through the great reorganization of rural Alberta into school divisions, it was estimated that rural teachers were owed more than $400,000 in long-overdue salaries. This illustrates the extent of the evil, and the urgency of the service, which John and the A.T.A. had been rendering in this field.

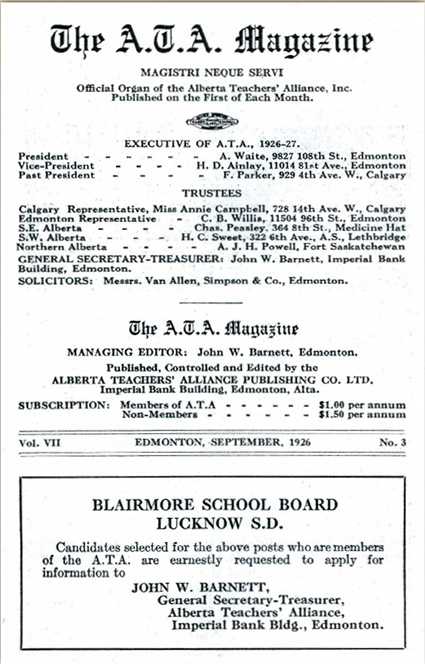

The September 1926 issue of The ATA Magazine (volume VII, number 3) featured the above notice warning teachers about seeking employment with the Blairmore School Board.

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

Another—and much more complex—field of service comprised the protection of the teacher’s tenure rights. A teacher could be dismissed because she did not teach Sunday school, or because she went to dances, or because she made friends in one family rather than another, or because the school board wanted a change. John Barnett’s classical example was that of a young teacher who was dismissed to make room for the daughter of Trustee B—an agreement having been reached that Chairman C’s herd would receive the services of Trustee B’s pedigree bull when the appointment was made.

Gradually a body of school law and departmental regulation was built up to curb such abuses of local power. Contracts were to be deemed continuous until terminated by proper process; the teacher must be given a week’s notice of a meeting with the board at which her interests could be defended. If the teacher still felt she had a grievance, she could ask the Department for a hearing before a Board of Reference, consisting of a judge of the bench, a nominee of the A.T.A. and a nominee of the Alberta School Trustees Association. At such a hearing (and usually at the local hearing preceding) Barnett was the teacher’s advocate.

John did not jump brashly into such duties. As soon as the A.T.A. was incorporated, he wisely selected a young lawyer, heading his own firm, who would not price his services too highly and would be willing to give time and thought to teacher problems. The young lawyer was George H. Van Allen, who for a modest annual retainer gave excellent guidance to Barnett and the young organization. In the 1930 provincial election, Allen was elected to the legislature on the Liberal side, but his death about a year later in the early prime of his powers deprived the Alliance of a good and resourceful friend. His place was well filled, however, by his junior associate Mr. Carlton W. Clement.

The bulldog tenacity with which John Barnett, backed by his Executives, pursued the ideal of security of tenure for teachers is well illustrated by the Athabasca case (about 1930). The principal and high school teacher there was a man of good professional qualification for those times, with satisfactory inspectors’ reports behind him. He was teaching a mixed group of pupils from the town and surrounding pioneer area in grades nine, ten and eleven. The results of the June departmental examinations were disappointing to the school board, and the principal was dismissed. The Alliance opposed the dismissal because the reason was insufficient and because the board had deviated from the lawful dismissal procedure.

The matter was heard as civil action in the District and Appeal Courts of Alberta, with judgment against the teacher. However, the A.T.A. carried the teacher’s case to the Supreme Court of Canada, where judgment was reversed. The teacher by this time was long gone from Athabasca, but his costs were recovered and the strong arm of the Alliance was henceforth respected.

An earlier and more spectacular struggle involved the entire school staff of the town of Blairmore in 1926. Early that year, the Blairmore board decided that a new room would have to be added to the school at a cost of some $10,000. Instead of charging this sum to taxpayers, the board decided to recover the amount over a short period of years by reducing the salaries of the teachers. The intended victims of this outrage appealed to the A.T.A., and Barnett probably told them their contracts were continuous and could not be unilaterally voided in this manner. The dispute deteriorated badly as the board refused to meet Barnett or recognize him as the teachers’ agent. To them he was an outside agitator.

Eventually the board dismissed the teachers upon their refusal to accept new contracts at lower salaries, but erred in the dismissal procedure. The Alliance persuaded the teachers to remain in Blairmore and to report for duty on opening day in September 1926. Meanwhile, a meeting of teachers was called in Edmonton during the marking and summer school period, and it was decided to launch a Blairmore Fund. Many teachers pledged monthly cash contributions, and came through with them. The Canadian Teachers’ Federation (C.T.F.), at its annual conference, made a substantial gift. Alfred Waite of Edmonton was named treasurer of the Fund, which was used to pay monthly indemnities to the Blairmore teachers as long as they remained locked out of their jobs.

A small boxed announcement under the masthead of the A.T.A. Magazine gave notice that any teacher considering employment with the Blairmore School Board was to communicate first with the general secretary of the A.T.A. This was probably the first blacklisting ever done by the Alliance; it continued in effect for many months after the locked-out teachers had dispersed to other schools, and until the board acknowledged the right of teachers to be represented by their organization and its officers. The teachers who consented to stand firm at the focal point of this bitter fight deserve to have their names remembered.

A tenure case with a curious angle was that of a young principal at Smoky Lake, who received notice of a board meeting at which his impending dismissal would be discussed. This writer travelled with Barnett who, as usual, was acting as the teacher’s advocate. They were met enroute by the local inspector, who said: “John, you know me. I’m an A.T.A. man from away back, and I’m telling you. Don’t touch this case, it is dynamite.” John asked for further elucidation, but the inspector would say no more, whereupon John summed it up: “Well, you can take care of the Department’s interest in the matter. The board can take care of the taxpayer’s interest. I am here to take care of the teacher’s interest, and that is just what I am going to do.” And he did, at a well-conducted board meeting that lasted from 8 p.m. until 1 a.m. Sunday morning. No vote was taken at the meeting, but John was informed by phone within a few hours that the dismissal was withdrawn. The truth emerged a few months later, when the young principal was elected M.L.A. for the riding. Someone else had had political aspirations, and it had seemed a good idea to get the young principal out of the way.

Dr. Milton E. LaZerte

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

Perren Baker

—Archives of the Alberta Teachers’ Association

Not all the colorful incidents of the old days were concerned with salary or tenure. Out at Castor, a principal and teacher were both sued for damages to the education of two boys who had been suspended from school for repeated truancy. The claim was for $50 in respect of each boy against each teacher, a total of $200. Instead of backing down with apologies, the teachers contacted Barnett, and on his advice stood their ground. In the District Court, judgment was rendered in favor of the parents, but the A.T.A. carried it to the Appeal Court, which awarded judgment and cost in favour of the teachers.

Somewhere west of Edson, a male teacher was hauled into court for brutality to a boy pupil. John was there to defend the teacher. (He often did minor court jobs to keep legal costs down.) The victim was in the witness box and showed great blue bruises on his arms. Rising to cross-examine the student, John kept his left hand in his pocket. “Mr. J____ did that to you?” The boy replied: “Yes sir, he did!” Barnett responded in a gentle voice: “Dear me; let me see.” Taking a firm hold of the boy’s hand, John drew forth a handkerchief, damped it on his tongue, and rubbed it on the child’s discoloured arm. Without further word, John showed the blue-stained handkerchief to the magistrate.

Less happy ventures

It must not be supposed that the young Alliance went from strength to strength without any false starts, or discouraging setbacks.

From the beginning, there were enthusiasts who wanted a vigorous program of educational research, and before long provincial committees were set up for this purpose. As far back as 1926, Arthur Roseborough’s Edmonton committee did a competent research job on high school examination results and presented it to the 1927 A.G.M. But only a few delegates understood the report. There was no college or faculty of education in Alberta to which the study could be submitted. Its fate was predictable: the Executive delegation presented the education minister with the Roseborough research job and the minister passed it to the deputy minister, who filed it away.

In 1929, an indignant Research Committee from Calgary appeared before the provincial executive and complained that it had been given no assignment. The harassed executive, knee-deep in law cases and exiguous finances, proposed tenure clauses and other clauses. Members said they had no time and begged the committee to find itself an assignment.

Research committees always wanted money for statistical reports from Ottawa, for stationery and postage, while the Alliance was barely making ends meet and had none to spare. But the activity, frustrated at every turn, was not entirely wasted. It helped to create the mood of restlessness and the urge for progress, which bore fruit in the establishment of the School of Education at the University of Alberta. This happy development took place in 1929; the staff consisting of Dr. Milton E. LaZerte (principal) and Dr. Herbert E. Smith. Thereafter, educational research had a home.

From the earliest days, a teachers’ retirement plan was an issue. A committee of Calgary teachers, in which M.W. Brock (later provincial president) was active, gathered information and exerted pressure year after year. Ontario had pensions; Manitoba had them and British Columbia had them. In 1928, the Saskatchewan teachers got a fine new retirement act through the legislature. But the going was hard in Alberta. The U.F.A. caucus could not be shown that teachers, any more than farmers, should be taken care of in their old age. Finally, in the summer of 1929, Alberta Premier Brownlee, conscious of the conspicuous isolation of Alberta in the matter of pensions, took John Barnett aside. He asked John to keep his pension people quiet for a few months, so the government would not seem to be under pressure. Brownlee believed he could carry through a teachers’ retirement plan at the 1930 session of the legislature. With the Wall Street crash in October 1929, the fiscal condition of the province immediately became precarious, and in the depression that followed, nothing more was heard about teachers’ pensions. For a few destitute and old teachers, Perren Baker was able to secure an indigent allowance of $25–$30 a month.

In 1939, William Aberhart was persuaded to put through a skeleton plan that collected percentage contributions from all teachers and paid a flat rate to all teachers retiring after the date of the act. In 1941, addressing the opening session of our annual meeting, Premier Aberhart said that an adequate retirement plan for teachers must be introduced at an early date. Unfortunately he died before he got around to it, and it was not until 1948 that his successor, Ernest Manning, made good the pledge.

Photo of Ernest Manning: Provincial Secretary for the Social Credit Party of Alberta (circa 1936), later Premier of Alberta (Social Credit) (1943–1968), Photographic Collection, Provincial Archives of Alberta, object number A6629

The A.T.A. Bureau of Education

In 1922, a group of Edmonton teachers promoted the idea of serving the teachers by selling them outline courses in the high school subjects. The courses were to be compiled by graduate specialists, and were to guide the teachers in presenting, digesting and testing their subject matter so as to prepare classes for successfully meeting their departmental examinations. The idea fitted well into the theme of giving service to the membership, and was adopted by the annual general meeting.

So the A.T.A. Bureau of Education was set up. From the start, it needed the full-time supervision of an expert, and an active sales force, but it enjoyed neither. The graduate specialists wrote the courses on a cash-down and royalty agreement, and mimeographing of the courses began in a large way up in the Imperial Bank’s top floor. Two Edmonton teachers undertook to give “after-four” supervision at the production end. But when Barnett went out on his fall travels, he found that the Bureau of Education sales pitch simply confused the issue. Many teachers would pay out ten or fifteen dollars for the courses but grudged five dollars for A.T.A. membership, and they took umbrage when he said they could not have one without the other. As time went on, he felt like a dog with a can tied to its tail; so he jettisoned the Bureau of Education sales pitch and returned to building the membership. The Bureau then channeled its promotion through the A.T.A. Magazine and through stalls at the fall conventions.

But the fledgling never really got off the ground. Payments for material and labor fell into arrears; the course writers were unpaid; teachers who had made prepayments clamored for their courses. Barnett stuck grimly to his A.T.A. duties and let the teacher promoters flounder as they might. In 1927, the plight of the Bureau of Education became the ground for open revolt in the A.G.M. There were those who felt that Barnett was not equal to the job and that they should look for another man.

What happened as the hassle drew towards the “crunch” (as Churchill would say) was pure comedy. To explain it, one must tell that in those days there were a dozen or so men-teachers who lived so far in the backwoods that they could not join locals, but they loved to sit in at the A.G.M. and were recognized as members-at-large. They were permitted to group in sixes and to choose one of themselves as delegate. The delegate had full voting rights; the others might take the floor.

On the Wednesday evening of Easter week 1927, as we sat in the basement of McDougall Church, Edmonton, the air was electric and we knew that this was it. The debate closed steadily in on the shortcomings of the general secretary. A member-at-large rose to a point of order and it took twenty minutes to clear that away as the acrimony deepened. Presently, another member-at-large rose to a point of privilege. The chairman, who had a foot in the rebel camp, whispered to John: “What do we do?” John passed the chairman a huge, closed copy of Bourinot’s Rules of Order. It was one of a few unkind acts of Barnett remembered against him.

The meeting floundered on, until at the moment of decision the delegate of the members-at-large rose and spoke. He was Fred J. Bendle from parts unknown: “What does this Alliance need in its executive officer? Does it need a peddler of courses? It does not. Does it need a foreman for its mimeograph shop? It does not. Does it need a research man? It does not. I’ll tell you what it needs; the Alliance needs a Fighter. When I was in a dispute with the Boyle Crossing School Board, was it a course peddler or a mimeograph foreman or a research student who got me out of a jam? It was not. It was fighting John Barnett, and he is the man we need to lead this organization. Mr. Chairman, as a duly-appointed delegate of the members-at-large, I wish to move a vote of confidence in our general secretary: fighting John Barnett.”

After thirty-five years, one cannot swear to the exact phrases, but that was the sense of Bendle’s speech, delivered with the Celtic passion and sharp articulation of a Swansea Welshman. The motion was seconded and carried handsomely. One of the malcontents capped the comedy by growling, as the meeting broke up: “Some of these members-at-large have no business being at large.”

The Bureau of Education lingered on, a source of worry and humiliation to the A.T.A. until in 1931 its assets and liabilities were taken over by W. Clarence Richards of the Institute of Applied Art. Mr. Richards is well remembered as a teacher of Victoria High School for many years. The Bureau may serve as a horrible example of the sort of enterprise not to be undertaken by a teachers’ organization in its early infancy.

Towards the light

Charles Stewart, Premier of Alberta (Liberal) (1917–1921), Photographic Collection, Provincial Archives of Alberta, object number A436

As far back as the Charles Stewart Liberal administration, the minimum teaching salary in Alberta was $840 per annum. In Manitoba there was no minimum (until during World War II, a minimum of $500 was set in a desperate bid to get teachers). In Saskatchewan it was $720. Thus it is quite understandable that Minister of Education Perren Baker gave scant attention to the Alliance’s pressure for a $1,000 minimum. Nevertheless the time was to come when the derided $840 stood between many rural teachers and penury, for there were hundreds of school districts in the Hungry Thirties that wanted to pay much less. But the legal clause covering the $840 minimum only allowed payment below that figure subject to the consent of the minister. As the Depression deepened, many boards pleaded with the minister for just such consent. Barnett contested each board request on its own merits and many were rejected. It is true that there was a massive decline in the economic status of Alberta teachers during that dark time and that some school boards almost found pleasure in their parsimony.

One small town out on the St. Paul line surpassed all others by cutting costs so fine that it voted to waive school taxes entirely and operate on the government grant. The board foolishly allowed the news to leak out to the Edmonton Journal. The department pounced on the board and firmly disciplined it.

The situation in Saskatchewan, where the teacher organization was defunct, was known to the rural teachers of Alberta. In August 1940, this writer bought a newspaper in Regina, which contained columns of teacher wanted notices. This ad (with a fictitious name) was typical: GOPHER DOME S.D. 9999 requires teacher grades 1 to 8. Salary $720, $400 cash.

The $720 was a gesture of respect to the legal minimum, but the $400 was a declaration of intention. Many small town high school principals with degrees were teaching for $600 a year. More than 2,000 Saskatchewan school boards were individually protected by Order-in-Council from legal action to recover unpaid salary.

One day in the mid-thirties, John dropped in at a rural school south of Lloydminster to canvass the teacher for a membership. The response was cordial: “See that white dot on the skyline. That’s a school in Saskatchewan. The man over there gets $420 a year and I get $840. Write me up.”

The flood of victory

For while the tired waves, vainly breaking,

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back, through creeks and inlets making,

Comes silent, flooding in, the main.

—“Say not the Struggle Naught availeth” by Arthur Hugh Clough, English educationalist and poet, 1819–1861

For the Alliance, and for John Barnett, the flood tide of victory came in mightily at last, and this was the manner of its coming …

The declining years of the U.F.A. administration (1934/35) were years of sheer frustration for the Alliance. The best efforts of their Executives had only partially stemmed the economic debacle for the teachers; one by one their small legal gains in security of tenure were annulled. To the A.T.A., it seemed that every interest of the teachers was tossed away to appease the U.F.A. caucus, angry and distraught at the loss of its leader and premier, John E. Brownlee. Then Perren Baker came forward with a proposal that rocked us all by its sheer unexpectedness. He would introduce a teaching profession bill, which would establish the A.T.A. as the legal entity of the teachers of Alberta, on a par with the medical, dental and legal professions. Perren Baker was a shrewd, down-to-earth thinker; he had doubtless made up his mind that the A.T.A. was here to stay, and that now was the time to remodel its image before the public. Hitherto, the A.T.A. had been disliked as a jumped-up, talkative, interfering busybody. It should now be made sober and respectable, and should learn more decorous ways. And in the great complex of educational reforms that followed the election of William Aberhart’s Social Credit government that is exactly what happened.

At all events, the Teaching Profession Act was passed. To bring the A.T.A. more into line with other professions (and to get rid of the fighting connotations of the old Alliance), we were now renamed the Alberta Teachers’ Association.

But Baker knew his limitations, and realised that he could not sell the caucus on the idea of compulsory membership of all teachers in the A.T.A. So he left it out. When Aberhart (himself a life-long teacher) came to power, John turned all his powers of persuasion upon him. The premier, taking counsel with his deputy, George F. McNally, was sympathetic to all teacher aspirations, but duly cautious.

“John, all these arguments you have given me in favor of compulsory membership are very convincing. But one thing you have not proved to me. Do the teachers want compulsory membership?” asked Aberhart.

“Sir,” replied John. “I appreciate the objection. Would it answer your question if we took a referendum of all the teachers in the province?”

It was agreed that this should be done. Time was limited, since (if any) it was already September and the amending legislation should be ready for the legislature in January. The premier would accept a complete referendum of all the teachers at all the fall conventions as an answer to his question. Ballots were prepared and experienced A.T.A. men were sent out to all conventions to expound the issue of compulsory membership and to conduct the ballot.

When the counting for the entire province was complete, the teachers had overwhelmingly endorsed compulsory membership. (John claimed 96 percent.) The work of John Barnett and many loyal associates had been well done through the long years, and Barnett’s place in the hearts of his fellow teachers was secure. That is how the flood tide came in.

Compulsory membership became law at the next legislative session. To fill the cup of our satisfaction, it was found possible and seemly within the scope of the School Ordinance and the Regulations of the Department for the Department to withhold membership dues of all teachers from the grants to school districts and pay them over in lump-sum cheques to our head office. John Barnett no longer had to comb the length and breadth of the province every year for funds to keep the Alliance alive. The old Alliance was dead—long live the Association!

He never quit

Since the preceding pages must have made it quite clear that writing about John Barnett was a labor of love, it would not be unseemly for the same biographer to give a glimpse of John’s faults and foibles, in order to round him out as a normal though eminent human being.

John had a certain gift of sardonic speech, uttered with a slightly Mephistophelean facial expression, which gave many people, especially young and transient lady teachers, an excuse to dislike him. Occasionally when he was tired or off guard, he allowed this mannerism to flare out when conversing with inspectors, principals and other seniors who were well able to flare right back, and so set up a permanent antagonism.

In fact, his critics never omitted to say “He antagonizes people.” In certain inspectorates and schools this made John’s promotion work much harder than it need have been. In order to get on terms of bonhomie with his teachers, John was frequently involved in bull sessions that swung into an exchange of good stories. He held his own very well until he tried too hard. While never, as one noted Canadian raconteur once said, the world’s worst story-teller, John did on occasion overload his stories with whimsy until the punchline fell like a dead fish.

On occasion too, John would be confronted at the A.G.M. or an executive session with an instruction or an order that he could not argue down and had to accept. If he did not like it as an A.T.A. policy, he would bury it in the files. His attitude, tacit but unmistakeable, was “I made this organization. I remake it every year. It’s mine, and no Johnny-come-lately is going to take over any of it.” That was why, until his final year, he could not be persuaded to take a deputy-secretary into his office.

An honorary doctorate was awarded to Barnett by the University of Alberta for his distinguished services in education. Owing to his untimely death in 1947, it was a posthumous award. John never held an academic degree, and was not unconscious of the fact. In the long negotiations that eventually moved all teacher education out of the normal schools into the university, John was not obstructive but was, if anything, lukewarm. He used to say that any good man without a degree was better than any nincompoop with a degree, and one had to counter with the remark that a trained good horse is better than an untrained good horse.

There is a cosy little theatre in the heart of London named The Windmill. Its risqué shows went on without interruption by blitz or fire right through World War II. It still uses the slogan: “We Never Closed.” Of John Barnett, let it be said with equal truth and a touch of reverence: He never quit.